Museums are my sanctuary. Art is my religion.

A few years ago, as I walked into a museum and the sense of relief and excitement enveloped me, I thought “museums are my sanctuary”. I can’t recall if that was a thought I’d had precisely that way before. Perhaps a friend and I had discussed that phrase once or many times before? I just don’t recall. But at this point, that idea became more cohesive. My subsequent thought was something along the lines of “well, if museums are my sanctuary, would art be my religion?” I realized that in some very real way, the answer was yes, and I was happy about it. This began an internal dialog about what that meant, how art as my religion or museums as my sanctuaries, might be similar to or different from other religions or sanctuaries. Why did those terms seem to fit so tidily in my mind?

There’s a lot to unpack here. I can’t recall ever walking into an art museum until I was in my mid twenties, and then only as a passing event. Feeling connected to museums didn’t start until my thirties. They were really quite foreign to me. I remember in my earlier museum experiences, I wondered why I was really there, what I was supposed to think or feel, how long I was supposed to stay, or how I was supposed to move within the space. I remember visiting a few shows that knocked me out, because I was excited about the artists work. These were solo shows…Wayne Thiebaud, John Baldessari, Noah Purifoy. I also remember hearing about a Magritte show at LACMA that people had found extraordinary, one that Baldessari had designed. I had only recently even heard of Baldessari and the exhibition had occurred before I started visiting museums. What did it mean for a museum exhibition to be extraordinary? I had no idea, and I felt stupid for not knowing.

The early few shows that I visited and enjoyed created a desire to make museum going a habit. At one point, I purchased an annual pass at LACMA. Then another somewhere else. I don’t recall how I walked through museums. Was I rushing or taking time to look? How did I feel? Was it meditative or exciting? The evolution of my museum going was slow, so I don’t recall the nuances or transitions.

At some point in the last ten years, visiting museums took on a major importance. I need them. They feed my soul. My museum visits take on many forms. I often seek museums out when I’m traveling through a town, and have no idea what I’ll find inside. Other times, I plan to see a show a year in advance. More often than not, I visit museums alone, as I feel they are private experiences anyways. Still, I frequently visit museums with friends, and these visits can make for fun conversations and shared memories.

None of this reveals why I think of museums as my sanctuaries, so I should get there. The word sanctuary is defined as a place of refuge and protection, so there’s that. I think of sanctuaries as places for solace and inspiration, so there’s that too. There’s something more though, and this started happening for me as my museum visits became more frequent. Much like the physical hunger for sustenance, sanctuaries are often sought out when spiritual replenishment is needed. In this regard, museums fit the definition for me as well. Obviously, sanctuaries are foremost about connecting to, and therefore humbling yourself in front of, something bigger than yourself. Sanctuaries are sacred. Well, sacred has several definitions. One of which has to do with a God or gods. Another is simply worthy of awe and respect, and that is how I feel about museums.

The rules of awe and respect might play out a bit differently in a museum than in a sanctuary, but that would be true between the houses of different religions as well. I will clarify that museums are not about the supernatural for me, so in this sense they are different from other houses of worship. But museums are places to connect with something bigger than myself. Two things in particular stand out in that regard, humanity and time. When I’m in a museum, much like with religions, I’m able to look through the sands of time. Religions have histories and religious texts give readers a view of lives going back millennia. They can read of their fears and struggles, joys and celebrations. They can connect to ideas of how societies might best function, moral codes. They can process the inevitability of their own lives fading into history. Looking at art offers all of those gifts as well. From the earliest cave paintings, to the Sistine Chapel, to Donald Judd’s cubes, I can both hear and imagine what humans lives were like throughout the centuries. I can also discover how creative people think, feel and live in distant lands. People seem to have created in every society, and this offers a window in to their souls. What is it that Mark Twain said, “travel is fatal to prejudice”? Looking at art is its own form of travel, seeing how other people think about the human condition. How do they process the questions of their own existence? I can go into a museum and have some interaction with a Christian, a Buddhist, a Muslim, a Jew, and an Atheist without ever saying a word. I can learn about what people eat, where they work, how they think about money or legal systems. It’s all there, and this pleases my soul.

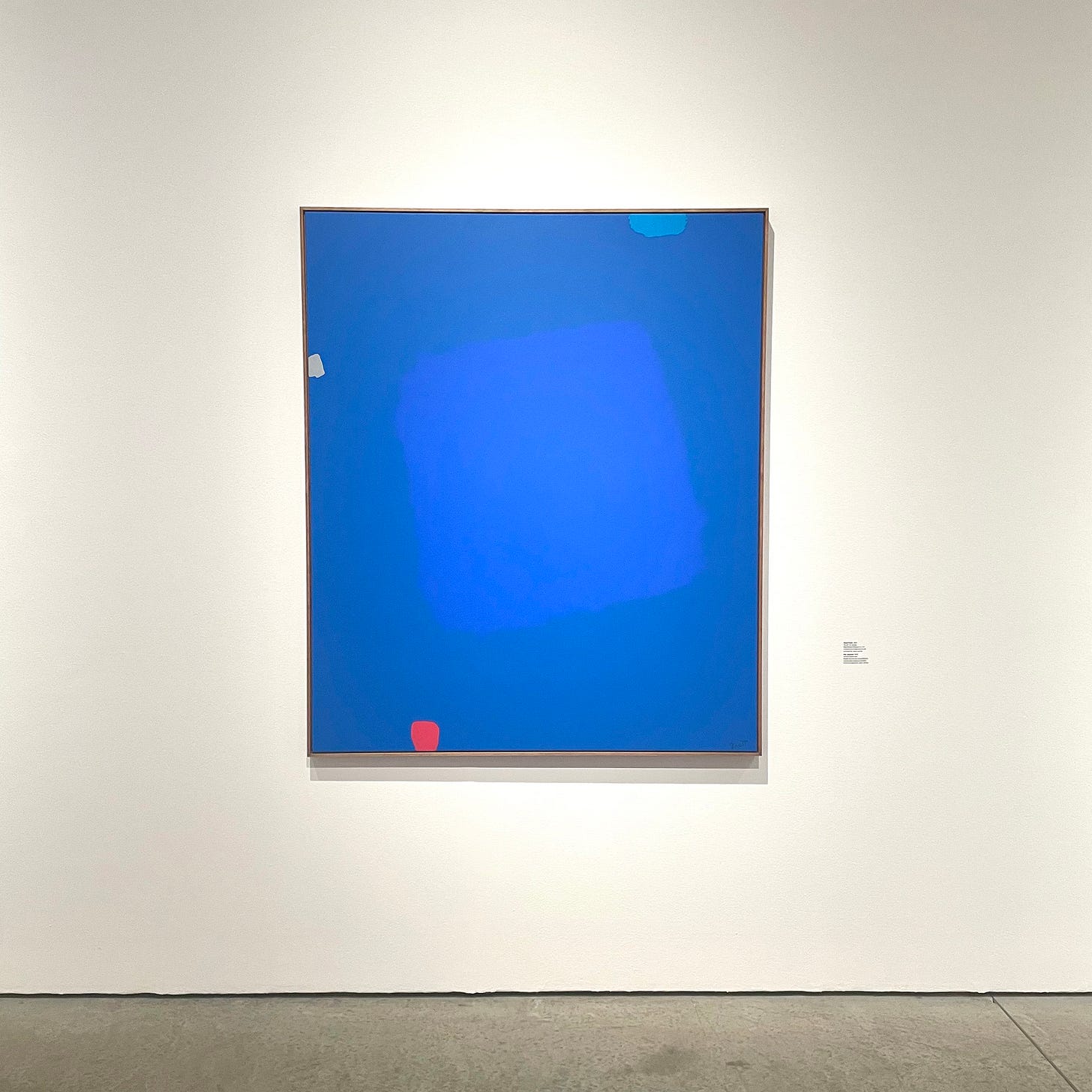

At the top of this post is an image of a painting by Dorothy Fratt, currently on display in a solo exhibition at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art. Many of you know I painted murals in a former life. One of my great strokes of luck was meeting my friend, Paul Wallace, a brilliant painter that went to my high school. I learned to paint from him as we painted murals together. We’ve shared countless conversations about color, composition, the role of art in our lives, etc.. Paul visited me in Phoenix a few weeks ago, and after more than thirty years of talking art together, we found ourselves staring at this blue painting. Just as we always have, we spent our day talking about what we saw. The variation in blue is totally different in person, and we noted how cameras just can’t seem to capture it. In reality, cameras can never capture it. You need to be there with the work. You need to feel your own scale in relation to the piece. Feel the space around you. Notice the light. Notice your emotions. I was grateful in that time for all the years that I’ve had with Paul. On this day, the museum galleries were almost empty and there was a friendly guard in the corner. How is it that I got so lucky to meet such a good person and learn how to paint from him, and find myself enjoying this quiet space with him three decades later?

I feel it’s important to mention how one might experience museums. Are there rules for the experiential element? Personally, I don’t think so. In fact, I believe this is why museums are for everyone. You don’t need to know anything to look at art. Knowing something about the artist, where they were from, as well as what school of thought they might have come from or what they were trying to say, can all inform and enrich the experience. But they are also beside the point that we are all human and we all have to process the events of our lives and the world around us. In addition, you’re not required to like or dislike anything in a museum, or even the museum itself. For instance, The Louvre is simply not a draw for me. I only went kicking and screaming the first time I was in Paris with some friends. I love the peacefulness of museums and I also know that I prefer museums of what I consider a manageable size. The Louvre is a magnificent museum but it is neither peaceful(crowds and more crowds), nor manageable. I pouted to my friends that I was not going to enjoy myself and didn’t want to see the Mona Lisa, which it’s important to admit is not my favorite painting. I’m allowed. And I was right. In fact, the experience of seeing the ultimate celebrity painting amongst all the selfie takers was soul crushing. It went against everything that means so much to me. On a side note, many people don’t know Mona Lisa became really famous after she was stolen and later discovered and returned. Spin has always existed.

Contrast this with another da Vinci experience I had only a week or so later. My friends and I had immersed ourselves in art in Amsterdam, Paris and Florence and I was floating on air. Our time together was ending, and I headed off on my own to Venice for a few days before heading back to the States. I found myself at the Gallerie dell'Accademia, where Vitruvian Man lives. I don’t have a photo, for good reason. This delicate drawing of a man with outstretched arms and legs, surrounded by a circle and a square, is heavily protected from the elements. The museum only shows it periodically, as any light can cause damage, and they display it in a closet sized, dark room that only one visitor at a time can fit into. I kid you not. I waited in a line of six or so individuals, each taking as much time as they needed. There was no rush. Everyone understood the seriousness of the moment. When it was my turn, I stepped inside. All black walls, I stood there alone with this masterpiece. At this moment, this drawing was all mine. I was the only one of eight billion people experiencing it. This could not have been more intimate. It also couldn’t have been less chaotic in comparison to the Mona Lisa fiasco a week earlier. In between the two, my friends and I saw Michelangelo’s David and seemingly infinite other inspiring works.

I’ve been writing about museums, but what of the idea of art as my religion? Well, this version of religion doesn’t happen to include the supernatural. The art I’m viewing remains in the natural world, so you might disagree with my use of the word religion. I totally understand. I suppose I can say I’m using the word in a metaphorical way, but that’s not entirely true either. I don’t worship art, but I do revere it. In my mind, it only exists within the framework of the physical, but its meaning surpasses that of nearly anything else in my life. Art has given me a way of looking at the world and moving within it. It has consoled me and challenged me. Like other religions, it has given me a sense of community as well. I feel connected to the artists I know and those I’ll never know. Art has given me many of my closest friends. It’s also introduced me to many new friends, as I’ve met collectors and gallery curators over the years. Art has also shown me the world and I’ve made what I considered pilgrimages to connect to art’s unfolding history.

If you aren’t an art person but think you might like to be, even just a little, I’d like to offer just a small bit of advise. I think it’s important not to force yourself to like any art or art experience out of a sense of obligation. It won’t work anyways, and will likely turn you away from looking at art. Some art will intrigue you. Some you’ll hate. It’s all good. It’s important to realize that sometimes art is about something that isn’t at first evident, and sometimes reading a wall card or watching a video about the artist might change your experience. Personally, I think it’s important to keep that in mind for moral reasons. Plus, challenging yourself is good. That said, I believe it’s hugely helpful to start with finding something you immediately like. Maybe you’ll want to go down a rabbit hole about Van Gogh or Vermeer after seeing one of their pieces somewhere. Also, move through the galleries of a museum at whatever pace you like. I see the same museum differently each time I visit and you likely will too. Whatever you do, please don’t feel stupid for whatever you don’t know. Children look at the world with a sense of awe. Unless someone tells them otherwise, they don’t think they’re stupid for not knowing everything. They more we know, the more we realize we know nothing. I don’t care if you don’t know the name of a single artist. This world is still for you and it’s an amazing one. If you need any pointers, feel free to send me a message and I’d be happy to help.